What a hostile bid for WBD tells us about credit markets, private financing, and risk appetite.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

Yesterday’s hostile bid for WBD draws a straight line from 1980s Wall Street excess to today’s resurgence of aggressive dealmaking

-

Paramount’s hostile move underscores the escalating pressure inside the modern media and streaming landscape

-

The financing behind the bid reflects classic peak-cycle leverage tactics resurfacing in today’s credit markets

-

The RJR Nabisco collapse offers a vivid historical warning about deals overloaded with debt

-

The recurring theme is that when leverage overtakes fundamentals, the ending rarely works in anyone’s favor

MY HOT TAKES

-

The credit environment is behaving like a late-cycle market stretched far past its comfort zone

-

Lenders are reaching for deals because they need deployment, not because the structures make sense

-

Hostile, highly leveraged bids are often signs of complacency disguised as confidence

-

Private credit’s abundance is encouraging risk that fundamentals may not be backing

-

History is signaling that leverage is becoming the protagonist again–and that’s when the trouble usually starts

-

You can quote me: “If Oreo cookies couldn’t survive peak leverage, what chance does Bugs Bunny have?”

Rabbit season! Full disclosure, I may have warped time–ever slightly–to make this tale a bit more interesting. Just bear with me. It is the late 1980s and I am a young–and completely clueless–Wall Street neophyte working on a bond trading desk. I was a budding Treasury trader fresh out of college with a degree in economics. I knew a few things about nothing that was really important, but I had swagger. To be completely honest, Treasury traders were pretty boring, which meant that most accomplished traders at the time were recovering gambling addicts / numbers savants. Easily, 4 out of 5 were capable of counting cards in Vegas and the fifth out of five was likely to be some sort of Bridge (the card game) champion at HIS beach club. These folks earned a living and passed the time bidding and offering billions of dollars worth of Treasury bonds, bills, and notes to insurance companies, pension funds, banks, and foreign central banks. Hey, it was a living, and the spread between bid and ask was big enough to earn lots of easy money, if you could keep your head on straight.

The real action was on the other side of the trading floor. That was where the Junk Bond desk existed. That was where all the cool folks were. They always looked like they were having fun. They were, by far, the best dressed folks on the floor. They had the most decadent parties, which we were invited to from time to time. I was friendly with a few of them, and I am pretty sure each one of my friends never actually paid for a parking spot in Manhattan. They simply double-parked all day, racking up tickets only to get reimbursed by the firm as a legitimate expense. Can you tell by now that it was a time of high excess?

Imagine a trading floor full of hundreds if not thousands of folks staring at piles of green-screen monitors with flashing numbers. The news tape scrolled on the walls with large dot matrix screens and a large ticker tape buzzed around the office. It was the “old days,” really. But that was it. You might see a bit of important news flash by and you literally had to jump out of your seat and follow it across the trading floor. That was step 1. Step 2 was to call every person you knew to confirm the story. This was obviously pre Bloomberg. Actually, there was 1 Bloomberg terminal shared by the entire fixed income group. It sat next to the Quotron which was the only way to get a stock market quote. That too was a shared resource. It was crazy, but it was a living, and being a bit of a math nerd, it kind of suited me. Then one day it happened.

It was October of 1988, a year after that fateful day where the stock market collapsed and the Dow plunged some 22% in a single day. Stocks spent an entire year clawing back some of the losses, but the wounds were still fresh and investors were still far under water. Stocks were kind-of cheap. What do folks like to do when stocks are cheap? Well, they like to buy them. If you really had guts, you might try to buy an entire public company and take it private. You wouldn’t have to spend your own money–no way–it was a job for OPM, short for Other Peoples’ Money. You could simply borrow the money to buy a public company. Banks would happily lend you money in bridge loans. Once the company was bought, you simply floated a bunch of bonds, loosely secured by the now-private company, to pay the banks back. Because the acquiring person or group put up very little of their own money, a successful eventual exit could return huge returns on invested capital. This was a classic leveraged-buy out. Oh, did I forget to tell you what happened on the date, almost a year to the day after Black Monday? Sorry, RJR Nabisco announced its intention to go private in a management buyout. Yep, I chased the news report all the way to the Junk Bond Department where one of my friends in his 3-piece bespoke-tailored suit explained that it would be a leveraged buyout and that every big player on Wall Street was after it.

Fast forward to today, and while the world looks different, the outlines feel familiar. Cue the Batman/ Dark Knight theme song. The Warner Bros. Discovery process began quietly late last summer when the company initiated what insiders called a “strategic alternatives review.” That is code for something bigger. Given the debt load from the 2022 merger and the intense pressure of the streaming wars, the board signaled it was open to either selling assets or considering a broader transaction. Rival Paramount was the first to approach with serious intent. Their initial talks were probably friendly with financial models exchanged, synergy slides drafted, bankers whispering about integrating CBS, Paramount+, and the Warner/HBO library. But Paramount’s capital structure complicated things, and the negotiations cooled.

Then Netflix entered the race. Their offer was cleaner, balance-sheet-ready, and operationally straightforward. For a brief moment, it appeared Netflix had secured preferred-suitor status. Lawyers began drafting language. The board seemed aligned. Paramount appeared sidelined.

Until this morning. Paramount returned not with a sweeter offer, but with the same headline valuation they had floated during the earlier friendly talks–only this time delivered as a full-throated, hostile bid. The price didn’t change, but the intent did. By taking the offer public and bypassing WBD’s board entirely, Paramount effectively forced the company into the spotlight, leaving its directors no choice but to respond on the record. That alone tells you how determined Paramount is to stay in this fight.

What makes the bid even more notable is the financing now sitting behind it. Paramount appears to have assembled a more aggressive and fully committed package than it had during the initial negotiations. Two major commercial banks have reportedly provided bridge commitments, and a consortium of private financiers, including credit funds, family offices, and, according to multiple outlets, even a politically connected family member in the White House orbit, has stepped in to secure the equity backstop. The structure features a multibillion-dollar bridge loan, mezzanine tranches at elevated yields, and enough committed capital to give the bid credibility despite Paramount’s own leveraged balance sheet. It is a bid designed not just to compete with Netflix, but to corner WBD into a decision.

This is classic late-cycle deal construction: high premium, aggressive financing, and a group of lenders willing to stretch because attractive deals are scarce. Loan demand is enormous right now–private credit funds alone are sitting on hundreds of billions of dry powder–and commercial banks are hungry for fee income after two slow years. Meanwhile, the supply of quality companies willing to sell is thin. When demand overwhelms supply, pricing adjusts. And in M&A, “pricing” often means “risk.” Terms loosen. Leverage increases. Investors convince themselves their models account for everything. My close followers know that I have brought up this concern on numerous occasions recently, and for some strange reason watching the story unfold during today’s session gave me a sort of deja déjà vu vibe. 😰

The RJR saga ultimately became the definitive case study in what happens when leverage mania outruns economic reality. KKR “won” the bidding war only by piling on a record-setting amount of debt at the very peak of 1980s LBO excess, and the company collapsed under the weight of that financing almost immediately. The promised turnaround never came; instead, RJR spent years selling assets, cutting jobs, and clawing for liquidity just to service the obligations that had been stacked onto it. In hindsight, the deal wasn’t just a failure–it was a signal that the market had reached its limit, a preview of the junk-bond unraveling that followed. It showed, in painful detail, how peak-cycle behavior and easy money can produce transactions that look brilliant in pitch books and impossible in practice.

As Paramount presses forward with a hostile bid for WBD, financed with aggressive structures in a market hungry for yield, it is fair to ask whether we are approaching a similar inflection point. Are lenders stretching because the opportunity is truly compelling, or because the alternatives are insufficient? When the financing tail starts wagging the strategic dog, history has shown that outcomes can turn quickly.

We’ve seen cycles like this before. And while today’s players carry streaming apps instead of cigarettes, the fundamental dynamics haven’t changed. When leverage becomes the story, it rarely delivers a happy ending. RJR didn’t just make tobacco products, it made Oreos, Ritz, and Chips Ahoy, household brands that ended up sold off piece by piece to service the debt that financed the takeover. It was such a vivid unraveling that the book Barbarians at the Gate, published in 1989, became an instant classic and remains one of the best-selling business books of all time. Decades later, it’s still required reading because the lesson refuses to grow old: when financial engineering overwhelms business fundamentals, it doesn’t matter whether the collateral is cigarettes, cookies, or streaming libraries–the math eventually calls your bluff. 👀

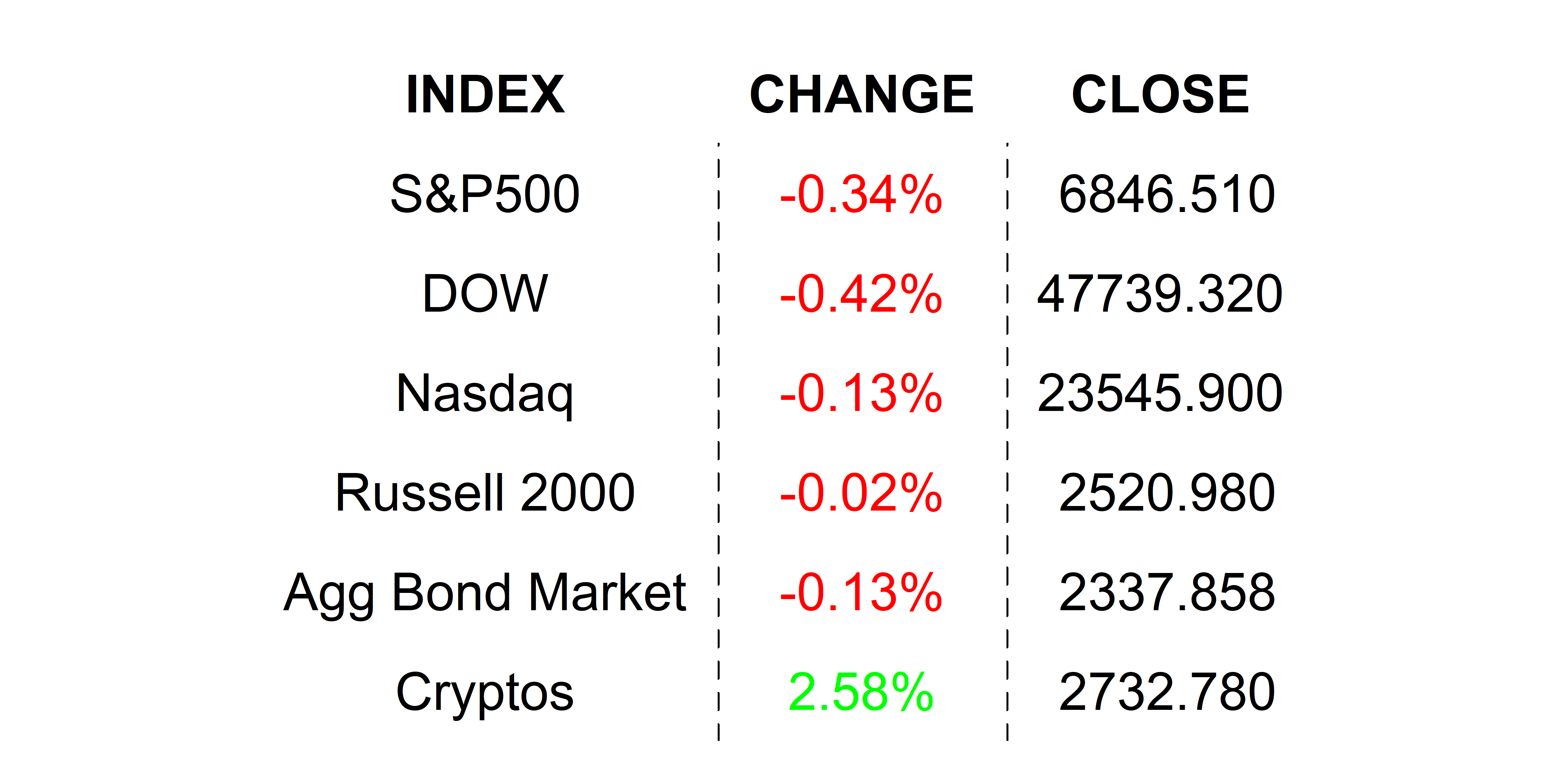

YESTERDAY’S MARKETS

Stocks lost ground today in the vacuum ahead of the FOMC meeting as investors brace for what is being bandied about in the media as a “hawkish” rate cut. Paramount’s hostile bid for WBD has traders wondering if the suitor is Batman nemesis Joker in Bugs Bunny disguise–or perhaps Elmer Fudd. Treasury yields climbed today as investors looked beyond this FOMC meeting and contemplated a less-dovish Fed in 2026–peak rate anxiety.

NEXT UP

-

NFIB Small Business Optimism (November) is expected to have gained slightly to 98.3 from 98.2.

-

Leading Economic Index (September) may have slipped by -0.3%.

-

JOLTS Job Openings (October) probably amounted to 7.117 million vacancies.

-

The FOMC meeting starts today, but markets will have to wait AND SPECULATE until tomorrow to learn about policy, and most importantly, the body language around the expected cut.

-

Important earnings today: Autozone, Campbells, AeroVironment, and GameStop.

.png)