History shows acquirers often overpay in emotional bidding wars. Here’s why this media battle may follow the same script.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

Competitive pressure and ego nearly led to overpaying for a target, only to have disciplined financial analysis ultimately halt the deal. The lesson of restraint in capital allocation became formative and enduring.

-

The academic concept of hubris bidding, explaining how overconfidence and imperfect information cause acquirers to systematically overestimate value. In competitive auctions, the winner is often the party that most misjudges intrinsic worth.

-

Cited empirical research shows that target shareholders typically capture the bulk of takeover gains, while acquiring shareholders frequently experience long-term underperformance. The premium is realized immediately by sellers, while the financial burden remains with buyers.

-

Hostile elements shift the focus from valuation discipline to competitive pride. Once ego enters the equation, financial modeling often becomes secondary.

-

Escalating offer prices, optimistic synergy assumptions, and complex financial structuring can erode the strength of the combined company’s capital structure. An initial stock price surge may obscure longer-term risks tied to leverage and integration challenges.

MY HOT TAKES

-

Investors must maintain discipline in takeover situations, especially when competitive pressure intensifies. The most powerful move in an overheated auction is often restraint, not escalation.

-

Focus relentlessly on price and intrinsic value, not strategic narratives or promised synergies. Every incremental dollar above fair value transfers wealth from acquirer shareholders to the seller.

-

Assume that bidding wars amplify overconfidence and weaken valuation rigor. Competitive environments should trigger stricter underwriting standards, not looser ones.

-

Treat short-term stock pops following takeover announcements with skepticism. Immediate premium realization does not eliminate long-term integration, leverage, or execution risk embedded in the combined entity.

-

Recognize that ego and narrative momentum are persistent forces in capital markets. Sound capital allocation requires separating the desire to win from the obligation to preserve shareholder value.

-

You can quote me: “In auctions, the winner is usually the one who most overestimates value–that’s not cynicism, it’s just math.”

Blinded by emotions. Picture this. I am driving with my family to Disney World in Florida and I have to pull over to take an important phone call. Back on the road. Another phone call. Back on the road. Ultimately, I had to get on a plane and leave my family on vacation to travel back up to New York for a 1 hour investment meeting. What followed the meeting was something I only experienced once in my 35-plus year career in finance. Bankers and financiers literally followed me in the men’s room and out to my limo–paid for by some of those bankers. They were all saying things like “pick me to be the lead,” or “ let’s talk over the weekend.” All of them. It reminded me of a book I read a decade earlier: Barbarians at the Gate, by Bryan Burrough and John Helyar. Most people only knew about it because it was made into an HBO movie in the early nineties, but it was requisite reading for budding Wall Streeters and MBAs–I was both. 😂

It was probably some time around 2000 and I was leading a group of really bright scientists and business folks who were seeking to acquire a small optical networking company. We had pursued the company for months. The company had been around for a long time and had some really strong assets but the market was changing rapidly and the company needed a change in strategic direction and an injection of new technology. We were the perfect group to stage the takeover and moonshot valuation growth which was attractive to not only financial investors, but also the company’s founder who was struggling with several years of flat growth. The numbers worked out beautifully and we were able to line up top-tier private equity investors to get the deal done.

I had those weekend phone calls and, until this day, I am reminded by my wife and both kids about the vacation they spent with me ducking out of the It’s A Small World line to hide and take a call. This is a true story. We finally lined everything up and made our offer. The founder of the company was going to become fabulously wealthy and we were going to create even more upside in an instant. Offer was in and… … … crickets. I called the founder over and over. Just a week earlier I was in his living room talking about family. What happened? Another bidder came in and made him a better offer. What the *&#@! 😡

No problem. The powerful financial syndicate I put together convened at our legal counsel's office. We were determined to win. Our strategy was bulletproof and we could already taste our success. When asked what I thought we should do, I threw out a higher offer price that I thought could win us the deal. Most of the room agreed in an instant. I had to go work up the offer letter and one of the most prominent investors followed me out and asked me “why should we pay so much–have you looked at the economics at that valuation?” At that moment, I knew that I was guilty of committing what I had so many times counseled others to avoid. I was overcome with hubris and was focused on winning at any price. I went home to work on the economics and realized that the numbers would simply not work at the new offer. I called off the deal. It was painful. Was it the one that got away? That was over 25 years ago, but that lesson never left me.

I hit the ground running after the long weekend determined to write about last Friday’s cool inflation print. I was going to detail how inflation continues to normalize and how that changes the calculus of the Fed and rate policy. Sorry to disappoint you, but I couldn’t help but get drawn back into the emotionally-charged love triangle between Netflix, Paramount Skydance, and Warner Brothers Discovery. This morning, Bloomberg first reported that Warner has agreed to let Paramount have 7 days to have another crack at the apple after Paramount agreed to certain concessions and improve the economics of their offer. That is code for “paying more;” the latest bid is now $31 per share. There it goes again. I can’t get the failed LBO of RJR Nabisco out of my head–I can literally see Ross Johnson’s face in my mind.

When Paramount first announced that they would be mounting a hostile tender offer of Warner Bros. That is when the psychology changed. I knew that this is no longer about discounted cash flow models and strategic fit, especially given the type of financial backing lined up by Paramount. This is about winning. And when winning becomes the objective, shareholders often lose.

There is an entire body of academic literature around what is known as hubris bidding. Richard Roll formalized it in 1986 with what he called the “hubris hypothesis” (Roll, Richard. 1986. “The Hubris Hypothesis of Corporate Takeovers.” Journal of Business 59, no. 2 (Part 1): 197–216.) The idea is simple but powerful: managers systematically overestimate their ability to create value and therefore overpay in takeovers. If two rational bidders compete in an auction with imperfect information, the winner is the one who most overestimates the value of the asset. That is not a motivational poster–it’s just math, stupid. 😉

Empirical work backs it up. Moeller, Schlingemann, and Stulz (Moeller, Sara B., Frederik P. Schlingemann, and René M. Stulz. 2004. “Firm Size and the Gains from Acquisitions.” Journal of Financial Economics 73, no. 2 (August): 201–228.) examined thousands of acquisitions and found that acquiring firm shareholders, particularly in large deals during merger waves, experienced significant wealth destruction around announcements. In one widely cited study, they documented tens of billions of dollars in aggregate losses to acquiring shareholders in just a few years around the turn of the millennium. 🙋 Targets, on the other hand, captured the lion’s share of the gains. The premium accrues quickly. The pain for the acquirer is often slow and steady.

We have seen it in real life. AOL and Time Warner in 2000. A deal born at the peak of narrative velocity. Synergies were promised (they always are in M&A deals). The stock-for-stock currency felt limitless. We were literally overpaying with over-valued stock! What followed were massive write-downs and years of underperformance. Hewlett-Packard’s acquisition of Autonomy in 2011 is another cautionary tale. The premium was rich. The confidence was high. The impairment that followed was staggering. Even Quaker Oats buying Snapple in the 1990s serves as a reminder that a “strategic fit” does not immunize a bidder from overpaying when competitive pressure mounts.

This is the pattern. The target celebrates. The acquirer justifies. And shareholders of the winner cross their fingers. Now, let’s bring it back to today. If Warner ultimately folds into Paramount as a result of an escalating bidding contest, Warner shareholders may enjoy a short-term pop. Premium realized. Champagne poured. But if the underlying economics of the combined entity are stretched because Paramount had to sweeten the pot with a higher price, debt backstops, ticking fees, break-up reimbursements, and other forms of what I politely call financial voodoo, that short-term gain can evaporate inside the capital structure of the new entity.

Hot speculative capital has a way of making numbers “work” in the pitch book, and there is plenty of hot capital out there these days. Aggressive synergy assumptions. Optimistic cost savings. Revenue cross-pollination that looks gorgeous in Excel but has a limited shelf life in the real world. If the bid is emotionally driven, those assumptions are rarely conservative–trust me. 😉

And Netflix is not immune. If Netflix responds by upping the ante simply to avoid losing, it risks the same disease I almost caught in that legal office 25 years ago. The desire to win can overpower the discipline to walk away. That is how good companies do questionable deals. Not because they are foolish. Because they are human.

This is not about whether media consolidation makes strategic sense. It might. This is about price. In auctions, price is where the emotion hides. Every incremental dollar above intrinsic value transfers wealth from the acquirer’s shareholders to the seller. That is not cynical. It is arithmetic.

I can still see that conference room. I can still feel the temptation to add a few more dollars to the offer just to secure the prize. If I had done that, perhaps we would have “won.” But we would have owned an asset at a price that made the economics brittle. One macro hiccup. One integration stumble. One revenue miss. And the entire thesis would have cracked.

That is what concerns me here. This is unlikely to end well for shareholders of the eventual winner. History suggests that in competitive bidding environments, the target captures the upside and the acquirer absorbs the regret. If Warner shareholders end up holding shares in a newly combined Paramount born of emotional escalation, the initial sugar high may fade into the sober reality of leverage, integration risk, and synergy shortfalls.

Blinded by emotions? I have been there. The difference between a good deal and a bad one is often not strategy. It is restraint. And in bidding wars, restraint is usually the first casualty.

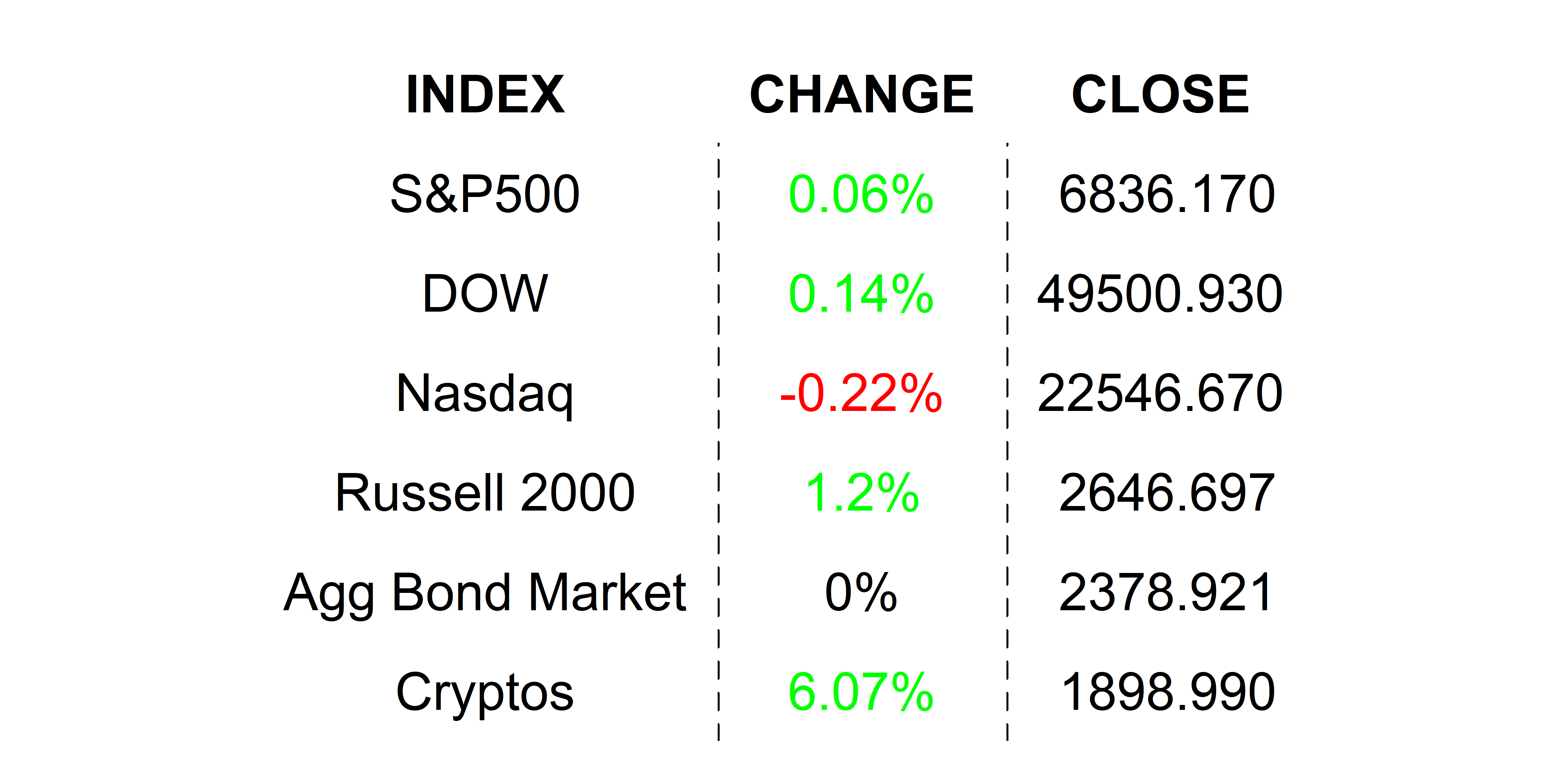

FRIDAY’S MARKETS

Stocks had a mixed close on Friday as investors turned optimistic about Fed policy in response to cooler than expected inflation numbers. Tech continues to feel pressure as investors rush out of overpriced tech stocks into overpriced value stocks. Gold and Bitcoin caught a bid after earlier-in-the-week pressure.

NEXT UP

-

Empire Manufacturing (Feb) came in above estimates at 7.1, lower than the January’s 7.7 print.

-

ADP NER Pulse (January 31st) ticked higher to 10.25k jobs from 7.75k new hires.

-

NAHB Housing Market Index (February) may have inched up to 38 from 37.

-

Fed speakers today: Goolsbee, Barr, and Daly.

-

Later this week, we will continue to get important earnings announcements in addition to Durable Goods Orders, more housing numbers, FOMC Meeting Minutes, Personal Income, Personal Spending, PCE Inflation Index, GDP, flash PMIs, and University of Michigan Sentiment. That’s a lot, so you better download the attached economic and earnings calendars to avoid getting caught on your heels.

.png)